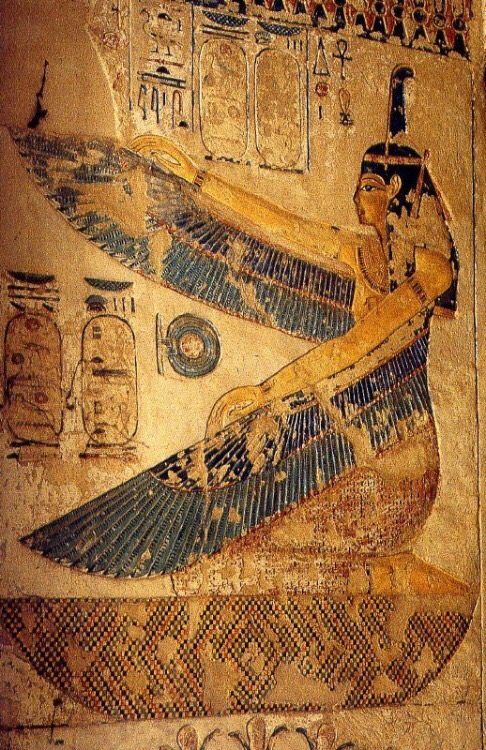

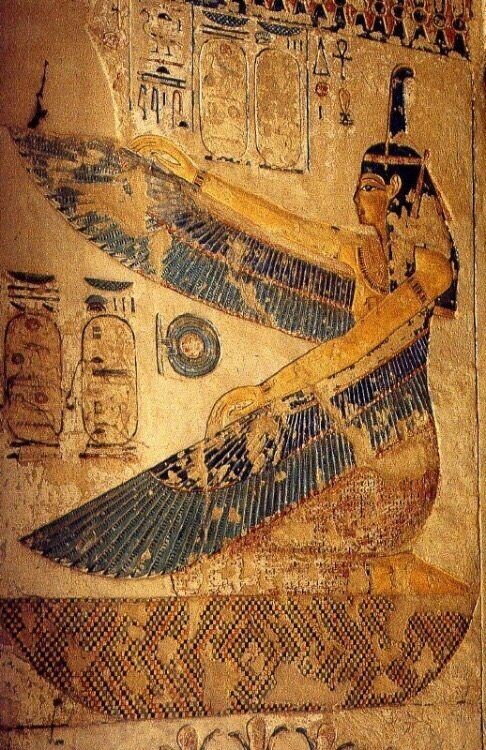

The concept of Ma’at was more than a word in Ancient Egypt; it was the lifeblood of society, a universal principle that touched all facets of life from religion to the operation of the state. I see it as the anchor of Egyptian culture, representing truth, balance, order, and righteousness. Ma’ap was not just an abstract ideal but was woven into the daily experience and governing system of every Egyptian, from the common farmer to the pharaoh.

Ma’at’s pervasiveness meant that society was always striving for equilibrium. Its tenets ensured that justice wasn’t just an abstract concept but a practical, living system. Every court decision, every law, and every social interaction was measured against the high standards set by Ma’at. This was a society deeply invested in maintaining balance, as it was believed that chaos, or ‘isfet,’ would ensue without a strong adherence to these principles.

Ma’at didn’t exist in isolation but was a reflection of divine will, believed to be established by the gods themselves. This divine connection elevated the pursuit of justice to a sacred duty. It was thought that maintaining Ma’at was necessary not only for the well-being of society but also for the cosmos at large. Failure in this respect would upset the natural balance of the universe, of which Egypt was considered a central part.

The Pharaoh: Supreme Authority in the Realm of Justice

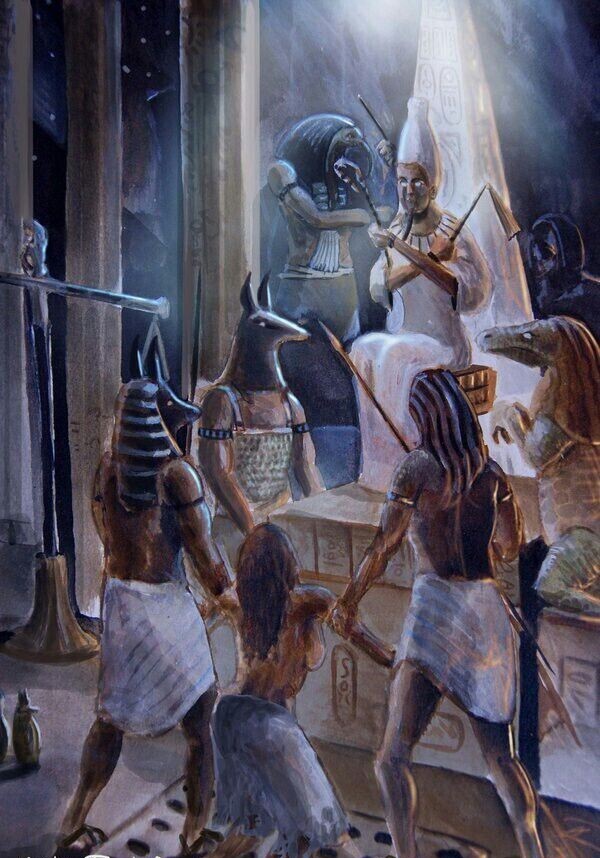

In Ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was revered not only as the head of state but also as the embodiment of divine order and the primary upholder of Ma’at. They didn’t just wear the crown; they were the living link between the people and the deities, entrusted with the colossal task of ensuring that justice permeated the land. This sacred duty was crucial, for the stability of the realm rested on their shoulders.

The pharaoh’s involvement in the judicial system underscores the gravity with which justice was regarded. While the pharaoh might not have presided over daily court proceedings, their influence was ever-present. Laws were issued under their authority, and they had the final say in legal matters, particularly those of significant consequence. The pharaoh’s decision could overturn a verdict or grant mercy, reflecting their central role in the administration of justice.

Even though they were seen as the ultimate judges, the pharaohs often delegated the daily administration of justice to their vizier. However, their symbolic presence loomed large, reminding all of Egypt that the law was a reflection of the will of the gods, as manifested through the pharaoh. By embodying Ma’at, the pharaoh ensured that the principles of truth, harmony, and balance were not mere ideals but tangible realities within the judicial system.

The Vizier: Ancient Egypt’s Chief Judicial Operator

Imagine a figure whose wisdom and authority are second only to the pharaoh, a person whose word could shape the destiny of many. The vizier in Ancient Egypt was exactly that. While the pharaoh was regarded as a deity and the ultimate judicial authority, he could not involve himself in the day-to-day legal affairs of a bustling civilization. This is where the vizier stepped in, shouldering the immense responsibility of overseeing the justice system.

The vizier was the head of the judicial system, a chief judge who was well-versed in the laws and decrees that kept Egyptian society running smoothly. It was his duty to ensure that the laws were enforced and the legal decisions were in alignment with the concept of Ma’at, upholding truth and order throughout the land.

Beyond presiding over important cases and managing the lower courts, the vizier also worked closely with other officials to ensure the legal decrees put forth by the pharaoh were carried out. This often meant traveling, sending messages, and making judgments that affected all levels of ancient Egyptian society.

In my role as your guide, I want to emphasize not just the position the vizier held, but the pivotal parts he played in maintaining the equilibrium of justice. Every major decision needed a signature from the vizier, reinforcing the trust placed in him by the citizens and the pharaoh.

Local Courts and Provincial Kenbet: The Judiciary’s Pillars

In ancient Egypt, the essence of maintaining order and addressing the daily legal concerns of its citizens lay in the structure of its local courts. These courts stood at the heart of each town and village, acting as the initial point of contact in the judiciary landscape. Such localized systems ensured that justice was accessible and that the legal process was woven into the fabric of community life. Presided over by local officials, including mayors and elders, these courts handled the majority of the disputes that arose, encompassing minor civil matters and low-level criminal cases.

In matters extending beyond the sphere of minor legal affairs, the provincial Kenbet courts came into play, serving as regional authorities that managed more significant legal issues. These courts were unique in their composition, consisting of local dignitaries and officials, individuals who possessed a deep understanding of local customs and prevailing laws. Their closeness to the citizenry made them adept at resolving conflicts that might disrupt the intrinsic balance upheld by Ma’at.

The shift from local courts to the Kenbet represented an escalation in the gravity of legal matters. Yet, even the Kenbet were sometimes overshadowed by cases of substantial weight and complexity. When such circumstances arose, the highest judicial power was summoned: the Great Kenbet. This apex court dealt with paramount cases that were too substantial for the lower courts to handle – issues like disputes involving nobility, or crimes that shook the societal order to its core. It was in the presence of the Great Kenbet that one would find the vizier presiding, flanked by high-ranking officials and priests, all intent on serving Ma’at to the fullest extent.

On the wings of these institutions flew the scribes and judges, the cornerstones of the judicial system. Their story is one of scrupulous record-keeping and the sage interpretation of laws. As I transition to exploring their roles, understand that it was here, amid logbooks and legal scrolls, judgments and jurisprudence, that the true art of ancient Egyptian justice found its voice.

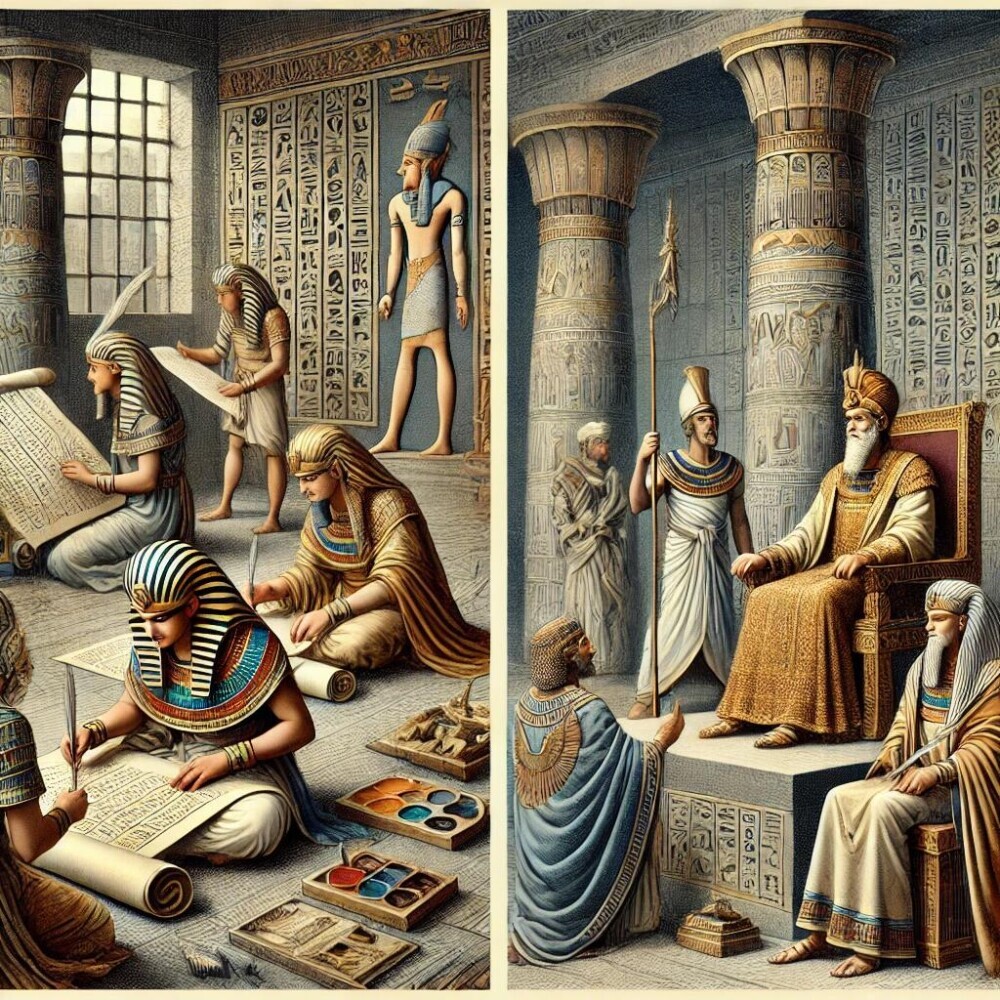

Scribes and Judges: Pillars of the Judicial Process

The Ancient Egyptian justice system relied heavily on meticulous record-keeping and the shrewd wisdom of its judges. To understand how justice was served, a closer look at the roles of scribes and judges is essential.

Picture a scribe, or “Sesh”, in the heart of a bustling courtroom, their skilled hands diligently recording the day’s proceedings. These professionals were far more than mere recorders; they were well-versed in the legal language and procedures of their time. Their records were the backbone of the justice system, creating a paper trail that both preserved the legal process and ensured transparency. Services were so invaluable, they were often regarded as extensions of the legal system itself.

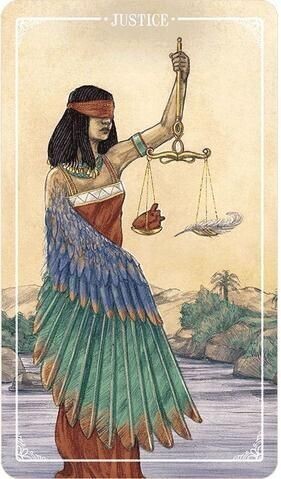

Shifting from the script to the scales, judges, known as “Kenebet”, were revered figures selected for their deep understanding of laws and commitment to integrity. Often hailing from backgrounds steeped in nobility or priesthood, they brought a wealth of knowledge and social insight to the bench. These judges were tasked with interpreting laws, weighing evidence, and delivering verdicts that aligned with the lofty ideals of Ma’at.

It’s the synergy between the scribes’ ink and the judges’ insight that allowed for the fair administration of justice in Ancient Egypt. Each verdict rendered was a testament to their combined efforts to maintain order and truth. This concept of justice was not just a civil service; it was a sacred duty, and those who served in these roles were careful to uphold their responsibilities with the gravity they deserved.

As scribes preserved the details of disputes and judgments, judges shaped the law’s application through their rulings. Which smoothly transitions us into the legal procedures and practices of Ancient Egypt. These included everything from how cases were initiated to the types of evidence considered, and even the variety of punishments meted out for different crimes.

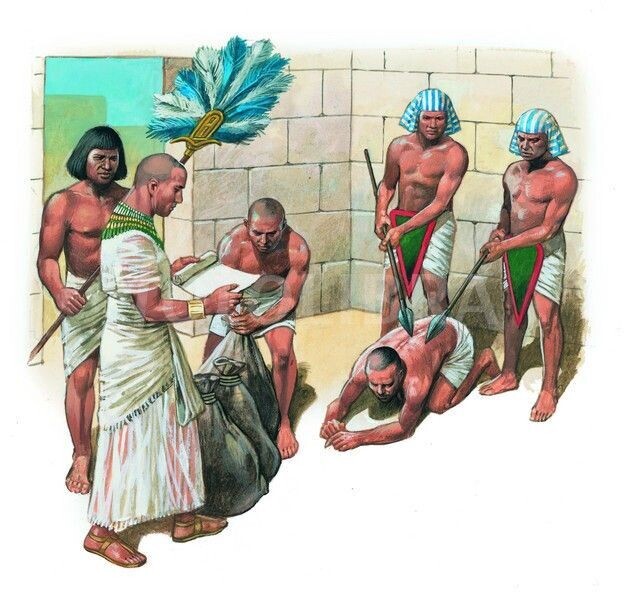

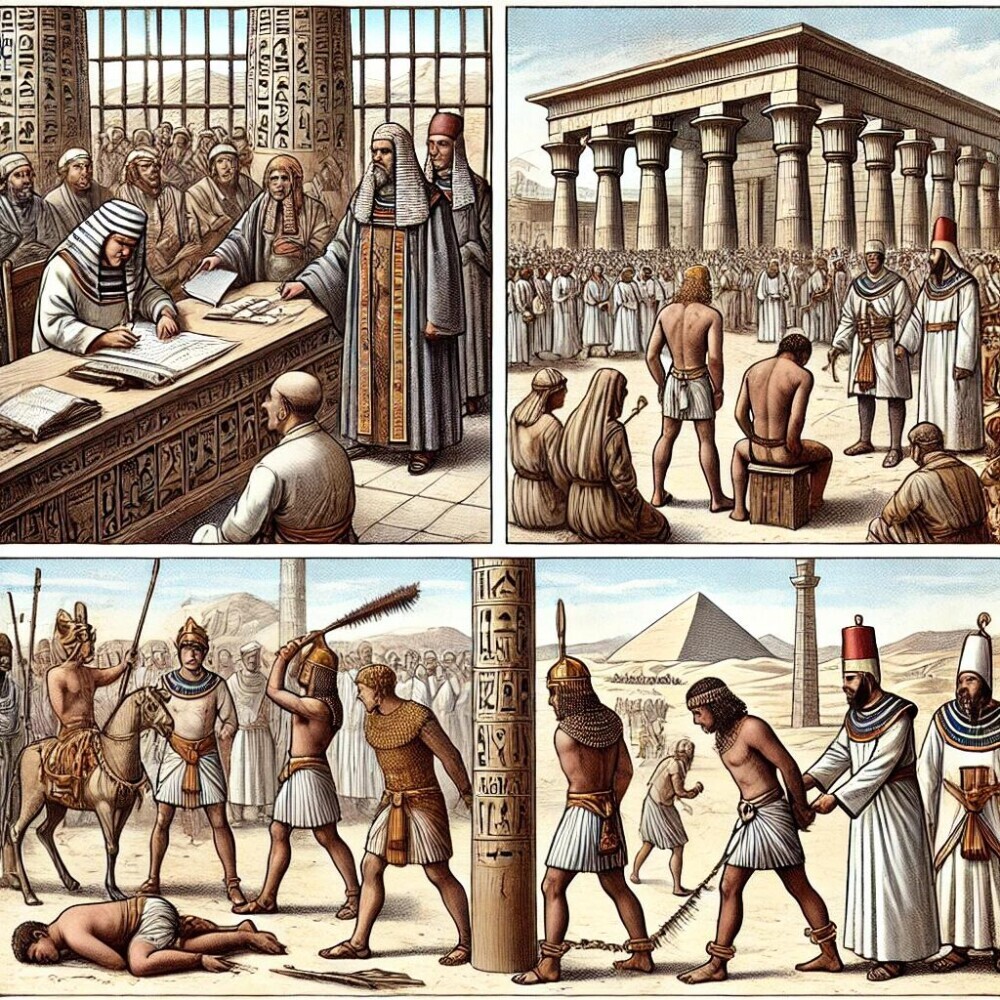

Decoding Legal Procedures: From Trials to Punishments

When you enter the world of ancient Egyptian jurisprudence, you quickly notice that their methods of handling legal disputes were quite sophisticated. Individuals could initiate legal proceedings by bringing forth complaints to local authorities. The system they employed ensured that truth was unearthed, making use of witness testimonies, written contracts, physical evidence, and in some cases, the accused’s oath to the gods.

The reliance on oaths demonstrated the seriousness with which Egyptians approached the truth. Invoking the gods’ names was not done lightly, for lying under oath would be an affront not only to the court but to the deities themselves. For the most perplexing cases, when human judgment seemed insufficient, an ordeal – perhaps an immersion in the Nile – was believed to reveal the truth through divine intervention.

With the facts laid bare, the courts then determined the appropriate punishment. For lesser crimes, monetary fines were common. However, punishments escalated with the gravity of the offenses with corporal punishment, such as whipping and mutilation, reserved for more grave transgressions. Incarceration was an option but used sparingly, primarily as a short-term measure. Ancient Egypt also understood the finality and severity of capital punishment, reserving the death penalty for the most egregious crimes such as murder or treason.

As a society that viewed harmony as sacred, punishments extended to measures designed to remove and rehabilitate. Exile, for instance, was both a punishment and a chance for the offender to start anew, away from the environment tied to their wrongdoing. Sentencing people to forced labor on state projects served a dual purpose: a punitive aspect and a means to contribute to society’s greater good.