I’m fascinated by how ancient cultures sought to make sense of the world around them, and Egyptian cosmogony provides a remarkable window into the Egyptian mind and spirit. These stories aren’t just tales; they were central to the ancient Egyptians, underpinning their religion, philosophy, and worldview.

Every culture has its own creation myth, and Ancient Egypt actually had several, each connected to a prominent city and its local deity. The Egyptians believed that through these myths, they could understand the origin of not only the physical world but also the social order and divine authority.

The primary narratives that explore these ancient beliefs include the Heliopolitan, Memphite, and Theban traditions. While distinct in details and characters, they share underlying themes of emergence, order, and the interplay of the elements.

Interestingly, the differences in these narratives are a testament to Egypt’s rich cultural diversity. Regional loyalties and the prominence of local temples influenced which version of the creation story became more dominant in an area. Yet, the essence of cosmic balance and the power of the gods unify these myths across the ancient Egyptian civilization.

The story that comes from Heliopolis, one of the chief cities of Ancient Egypt, sets the scene with the god Atum standing alone in the waters of chaos. As we move to the next section, I’ll delve into the evocative tale of Atum, the Benben stone, and the divine lineage that sprang from this singular creative act.

The Heliopolitan Creation Myth: Atum and the Benben Stone

In the ancient city of Heliopolis, a powerful narrative about the origins of the world took shape. Central to this story was Atum, a self-created deity who symbolizes the totality of the universe. Atum’s emergence marks the first event in the Heliopolitan creation myth, a narrative that provides profound insights into how Egyptians conceptualized the beginning of everything.

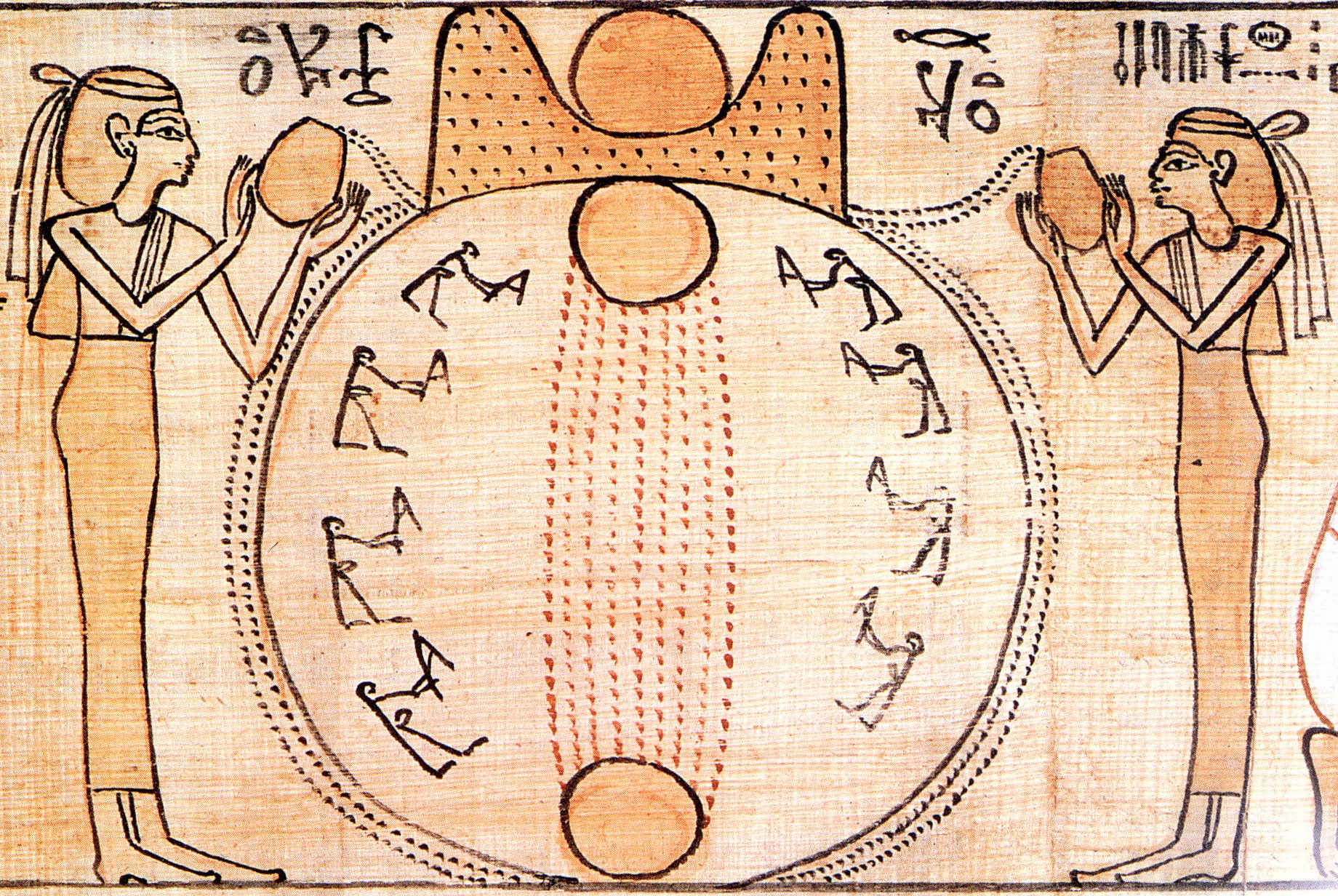

According to this myth, Atum rose from the chaotic primordial waters known as Nun. By standing on the Benben Stone, a sacred obelisk-like structure, Atum initiated the creation process. This stone not only represented the first solid ground but also served as the prototype for pyramids and obelisks, which were integral to Egyptian religious architecture.

The narrative unfolds with Atum engendering two deities from himself — Shu, embodying the air, and Tefnut, the deity of moisture. Their existence brought forth the principles of life, order, and stability. Atum’s act of creation by self-propagation sets the stage for the complex interrelationships among the gods that followed.

Ma’at, or the concept of cosmic order, is an underpinning theme in the myth. Maintaining Ma’at, which translates to order, harmony, and balance, was essential for the continual renewal of the world. The pharaoh’s role was integral in this, as he was seen as the earthly guardian of Ma’at, responsible for upholding the balance and preventing the descent into chaos.

The Memphite Theology: Ptah and the Word of Creation

Stepping into Memphis, the ancient capital, introduces us to another influential creation story starring Ptah, the patron god of artisans. Ptah didn’t just craft objects; he is said to have crafted the universe itself. This narrative, known as the Memphite theology, offers an alternative yet enriching angle to our understanding of Egyptian mythos.

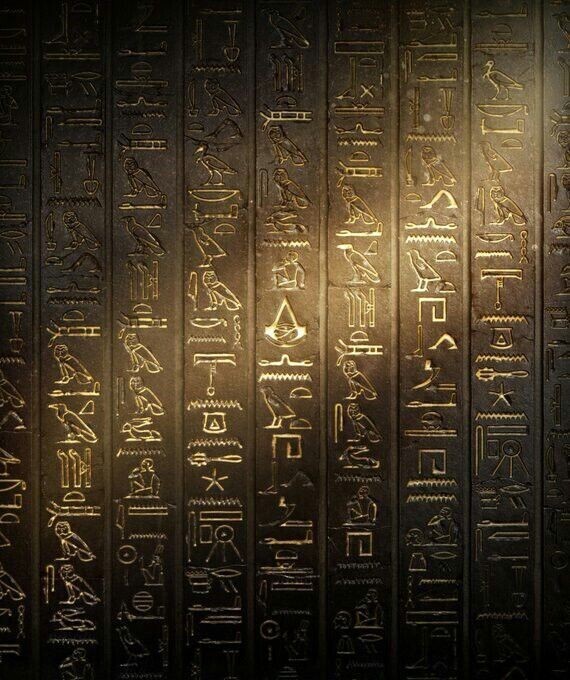

At the heart of the Memphite narrative stands a concept that might echo familiar themes from religions and philosophies worldwide: the power of the word and thought. Ancient texts suggest that Ptah created the world through heart and tongue – essentially through thought and word, an idea that precedes modern beliefs in the power of speech and intention.

Unlike the Heliopolitan focus on a physical emergence from a watery chaos, the Memphite theology emphasizes a more abstract process. It considers the mind and speech of Ptah as the source of creation, where each god is a manifestation of his creative command.

This perception of creation is fascinating as it intertwines with the role of craftsmen. Just as craftsmen create their works, Ptah is believed to have planned and executed the cosmos with precision – a nod to the highly valued skill of crafting in ancient Egyptian society.

Comparing the Memphite theology with other Egyptian myths reveals a layered and complex belief system, where different gods and processes converge to explain the cosmic origins. But the common thread across these narratives is the Egyptians’ quest to understand the universe and their place within it.

Unveiling the Layers: The Legacy of Egyptian Creation Myths

The Theban narrative of creation, featuring Amun and the Ogdoad, stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of myths that the ancient Egyptians used to explain the origins of the universe. As we review these myths, we see not just stories but a window into the values, beliefs, and understanding of the cosmos that ancient societies held.

Each myth, while unique in its characters and narrative, underscores a common drive to find order in chaos and to personify the natural world. The myths offered a framework for Egyptians to make sense of natural phenomena and life’s mysteries, giving rise to a vibrant culture steeped in ritual and symbolism.

Moreover, these creation stories have influenced modern perspectives on ancient wisdom and spirituality. They have provided a foundation for subsequent mythologies and continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike. By looking back at these ancient narratives, we glean insights into how early civilizations shaped their worldviews and laid the groundwork for today’s cultural and religious practices.

In closing, the Egyptian creation myths do more than paint a picture of how the ancients believed the world began; they encapsulate an entire worldview tied inextricably to the rhythms of nature and the unending human quest to understand our place in the universe.