I find it extraordinary to consider the sophistication of Ancient Egyptian education. This complex system has, throughout history, been a Springboard for a highly organized civilization. Its structure bore the weight of bureaucracy, empowered religious authorities, and fanned the flames of cultural evolution. My task here is not simply to list dates and facts. Rather, I seek to convey the gravity and relevance of Egypt’s educational framework as it relates to the pillars of society we recognize even today.

Education in Ancient Egypt wasn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. It was selective and calculated, aimed at grooming individuals for specific roles within a strict hierarchical system. At the heart of this system lay the revered scribes and scholars, whose rigorous training and distinguished knowledge positioned them as the backbone of civilization. The legacy they left behind has informed both historical insights and the progression of education as we know it.

With an eye to understanding this educational heritage, I’ll explore the purpose and practice of learning in Ancient Egypt. How did it contribute to maintaining an organized society and what advancements did it fuel? Join me as I unravel the significance of ancient Egyptian scholarly pursuits, from the broad-ranging curriculum of the House of Life to the individualized instruction within the halls of royal palaces.

The Cornerstones of Egyptian Society: Education’s Vital Role

Education’s impact on Ancient Egyptian society cannot be overstated. It wasn’t simply about learning to read and write; it was the foundation of a complex civilization. The structured hierarchy of Ancient Egypt rested on the shoulders of those who could navigate the written world. I aim to unpack how the spread of knowledge helped maintain the social order and enabled the smooth operation of what was one of the most intricate administrations of the ancient world.

Take, for instance, the roles of scribes and priests. These were more than just prestigious titles; they were the backbone of the society’s infrastructure. Scribes handled vital tasks, from tax collection to documenting royal commands, while priests not only tended to religious duties but also served as educators. Both relied heavily on their literacy to perform their functions effectively.

But education’s sphere of influence reached beyond the corridors of power. It served as a vessel to carry forward the richness of Egyptian culture. Historical accounts, religious beliefs, and scientific insights were all meticulously preserved and passed down through generations, ensuring the country’s legacy.

This culture of learning also facilitated Egypt’s remarkable scientific advances. The development of a calendar system, for example, was no small feat. It required an intricate understanding of astronomy and mathematics, disciplines that likely found their earliest roots in an educational setting.

From Temples to Tutors: The Realms of Egyptian Learning

The Ancient Egyptians crafted a multifaceted system of education that transcended mere literacy and instilled knowledge across various echelons of society. Central to this pursuit were the institutional bastions of learning, which fostered intellectual growth among the elite. These institutions not only upheld the sanctity of knowledge but also ensured its perpetuity through a structured pedagogy.

The House of Life, or Per Ankh, stood out as a vital center for education. Fixed within the precincts of temples, it served the dual purpose of safeguarding sacred texts and fostering scholarly discourse. Here, students delved into subjects that grasped the essence of their civilization – from the religious doctrines that forged their understanding of the cosmos to the medicinal practices that preserved life. Instruction within these walls was not merely about rote learning; it was an initiation into the proud lineage of Egyptian scholarship.

Parallel to the Houses of Life were the temple schools. These learning havens were pivotal to the religious education of priests who, in turn, imparted their knowledge to the next generation of scribes and administrative officials. Not only did these institutions function as centers of learning, but they also housed comprehensive libraries. They were treasure troves of knowledge, home to administrative records and scientific works that epitomized the Egyptian zest for order and understanding.

Whereas temple schools catered primarily to those within the clerical and scholastic realms, another more exclusive educational segment was the palace schools. Catered to needs of royalty and their courtiers, these schools offered customized curricula focusing on governance, diplomacy, and military strategy – subjects befitting future leaders. Noteworthy were the celebrated tutors hired from the upper echelons of officials and priests who provided a quality of education worthy of the governing elite.

In the following section, the journey continues as we explore the meticulous world of the scribes – the record keepers and administrators underpinning the very function of the kingdom.

The Scribal Arts: Pillars of Ancient Egyptian Administration

In Ancient Egypt, administration was an art meticulously conducted by the highly trained scribes, serving as the backbone of the kingdom’s complex bureaucratic system. As a class, scribes held the keys to literacy and learning, making them indispensable in the management of state affairs. Their role extended beyond mere record-keepers to that of custodians of culture and governance.

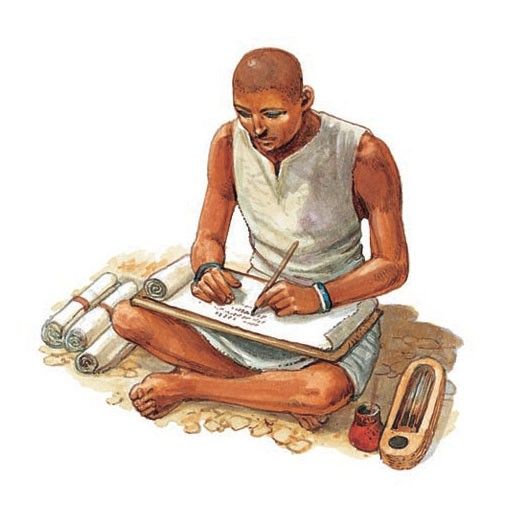

Education for scribes was a rigorous and esteemed process, with schools known as “Houses of Instruction” or “Schools of Scribes” offering extensive programs. Prospective scribes started their education as children, embarking on a journey that demanded dedication and precision. The curriculum not only required mastery of the hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts but also encompassed mathematics, grammar, and a range of administrative tasks.

Scribes were tasked with learning a variety of texts that embedded both practical knowledge and moral wisdom. Key among these texts were “The Instructions of Kagemni” and “The Maxims of Ptahhotep”, which were essentially guidebooks to professional and ethical conduct. These works underscored the importance the Egyptians placed on moral responsibility and behavioral norms for individuals serving in administrative capacities.

Instruction methods were firmly grounded in practical application and repetition. Students would meticulously copy texts to learn the intricacies of the written word and to absorb the comprehensive knowledge those texts contained. Mathematical training was not abstract but applied, preparing scribes for responsibilities such as land measurement, resource management, and labor organisation. Oral teaching methods complemented these exercises, as teachers verbally communicated knowledge and corrected their students’ work, instilling the need for accuracy and attention to detail.

As the students of the scribe schools progressed, those who showed aptitude might engage in higher learning, advancing Egypt’s knowledge base in various scholarly fields. This transition from foundational scribal training to scholarly study was seamless and highlighted the fluidity within Egyptian educational dynamics.

In Pursuit of Excellence: Advanced Learning and Scholarly Endeavors

While the scribes mastered the intricacies of administrative duties, another echelon of learned individuals in Ancient Egypt pursued advanced studies in various fields. These scholars, often drawn from the highest ranks of society, ventured into disciplines that many today regard as the forerunners to modern science, medicine, and engineering.

Medical training stood out, with institutions delving into the study of texts like the Ebers Papyrus, which is among the oldest preserved medical documents. Scholars learned about disease and treatments, blending empirical observation with spiritual beliefs. For surgical techniques, meticulous hands-on practice was paramount, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of the human body.

In astronomy and mathematics, Egyptian scholars’ work was nothing short of pioneering. They meticulously observed celestial movements to create calendars integral to agriculture and religious events. Additionally, their facility with numbers allowed for complex calculations and architectural plans that still fascinate engineers and mathematicians.

Architecture and engineering were, in fact, the cornerstones of the awe-inspiring structures we associate with Egypt today. Scholars in these fields grasped the principles of mechanical engineering and mastered construction techniques that enabled them to erect temples, pyramids, and monuments that have withstood millennia.

These scholarly pursuits produced individuals whose legacies transcend time. Imhotep, the architect of the Step Pyramid of Djoser, was also a skilled physician and is sometimes credited with compiling an early encyclopedia on medicine. As a polymath, his breadth of knowledge exemplified the respected status of scholars in Ancient Egypt.

Equally significant is the mythical god Thoth, revered as the deity of wisdom, writing, and science. He underscored the divine association of knowledge and served as the emblematic patron of all scribes and scholars, encapsulating the profound respect for learning in Egyptian culture.

The intellectual contributions of these scholars were profound, setting the stage for a tradition of inquiry and discovery. Their meticulous record-keeping and innovative approaches to challenges of their time laid a foundation that not only served their society but also provided valuable insights for generations to come.

Tools of the Trade: Resources and Texts in Egyptian Education

The scholars of Ancient Egypt owed much of their success to an array of educational materials and literary resources. Papyrus, crafted from the stalks of the plant that shared its name, was the most common writing surface. Esteemed for its durability and portability, it was the choice material for creating documents, compiling literary texts, and even crafting educational resources.

Ostraca presented a more economical alternative for practice scribing or jotting down casual notes. These pottery shards, often found in abundance, served as the notepad of the common student or scribe in training, evidencing their improvisational use of available resources.

Inks and brushes also played an essential role in the education system. Preparing ink from soot or ochre mixed with water, ancient Egyptian students would use reed brushes to transcribe characters onto their chosen mediums. This practice not only honed their calligraphy but also instilled in them the precision required for meticulous record-keeping.

Beyond the tools were the texts. Instructional literature, such as “The Instructions of Kagemni” and “The Maxims of Ptahhotep”, provided a blueprint for social behavior, a code of ethics for both professional and personal life. These works were cornerstone texts, aimed at guiding young scribes on a path of wisdom and integrity.

Religious texts, suffused with hymns, prayers, and detailed ritual instructions, functioned as both educational material and spiritual guide, reinforcing the centrality of religious practice in everyday life. Moreover, scientific and medical texts provided compilations of extensive knowledge on subjects like astronomy and medicine, serving as testimony to the Egyptians’ advancement in empirical understanding and methodology.

The accumulation of these materials and resources underscores the esteem with which education and knowledge were regarded in Ancient Egypt. They provide a window into a society where teaching and learning were infused with reverence, utility, and an enduring aspiration for enlightenment and proficiency.

Reflections on Ancient Knowledge: Implications for Modern Understanding

In the span of human history, education has consistently been a beacon of progress and a pillar of civilization. Ancient Egypt’s complex system of education, with its emphasis on literacy, vocational training, and scholarly inquiry, reveals the country’s deep appreciation for the power and value of knowledge. What can our modern educational framework glean from this ancient wisdom?

First and foremost, Egypt teaches us the importance of structured learning environments. Their ‘House of Life’ and temple schools didn’t just impart knowledge; they nurtured a community of learners and educators, much like our contemporary universities and research institutions.

Secondly, the Egyptian emphasis on practical application—be it through scribe schools or architectural stands as a testament to the enduring relevance of hands-on experience. This mirrors today’s educational trends that emphasize problem-solving, critical thinking skills, and real-world applications.

Furthermore, the exclusive nature of Ancient Egyptian education underscores the need for accessible learning in modern times. While we’ve made strides compared to the past, the Egyptian model highlights the importance of inclusivity and continues to inspire efforts to democratize education globally.

Lastly, the preservation and veneration of knowledge by the Egyptians through texts like “The Instructions of Kagemni” remind us of the value of historical and cultural literacy. As we forge ahead into a world increasingly dependent on technology and science, we must also remember to safeguard the humanities—our collective treasure trove of wisdom.

In essence, the dialogue between the past and present is ever-evolving, and the threads of ancient education continue to intertwine with our modern educational tapestry. By examining the remnants of Egypt’s renowned learning systems, we can appreciate their meticulous planning, diligent record-keeping, and cultural reverence—attributes that will always be relevant in an increasingly knowledge-based society.